1761-1836

Sarah Siddons © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

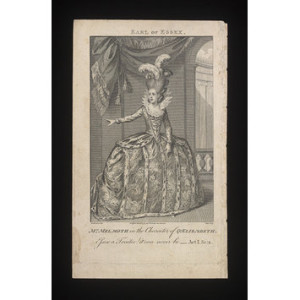

Elizabeth Whitlock Harvard Theatre Collection

Mrs. Elizabeth (or Eliza) Kemble Whitlock. was born in 1761 into the famous Kemble theatrical family; she was a sister to the famous Sarah Siddons. Elizabeth Kemble married Charles Whitlock and came with him the United States in 1793. According to Clapp, “Mrs. Whitlock was a striking and pleasing resemblance to her sister, possessing a full share of her noble air and elocutionary powers, with more amusing powers of conversation.”[1] According to John Bernard , Mrs. Whitelock [sic] “is said to have had a full share of the family good looks and acting ability.[2]

“Theatricus” praised Mrs. Whitlock as the “first actress in America,” and noted that she had “an unlimited command over the feelings of the spectators.” Theatricus went on at length about Mrs. Whitlock’s prowess:

To conclude, Mrs. Whitlock has a graceful carriage–her

pronunciation is animated; her voice and her countenance

are capable of every inflexion necessary to express the

most opposite emotions and passions, with the utmost

promptitude—her memory is so good and her application

so assiduous, as to leave her little in debt to the prompter’s aid.[3]

Mrs. Whitlock made her London debut at Drury Lane . In 1785, she married Charles Whitlock, manager of the Newcastle-upon Tyne circuit. When she and her husband were performing in Edinburgh, she was recruited by Thomas Wignell for the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia.[4]

In February of 1794 she made her first appearance on the Philadelphia stage one of her

Old Chestnut Street Theatre Public Domain Image

sister’s (Sarah Siddons) favorite characters: Isabella in Isabella; or The Fatal Marriage. [5] As Bernard recalls,

There were members of this company who must pass unrecorded. Here I found Mrs. Whitelock [sic], the sister of Mrs. Siddons, and allied to her in genius as well as in blood.[6]

In Julia Curtis’s article “John Joseph Stephen Leger Sollee’s Management of the Charleston Theatre,” she relates that, in 1794, Wignell brought the group to Philadelphia and then, “after an engagement for thirteen nights in Boston during the Fall of 1796, they arrived in Charleston.” [7] During the upcoming season at Charleston, Mrs. Whitlock would be described as “a brilliant, set in tin,’ because the rest of the company, with only a few exceptions, was “deplorably weak.”[8]

Park Theatre Public Domain Image

The Whitlocks returned to England for a time, and Ireland notes that in 1800, Elizabeth played again in London. After they returned to the United States, she and her husband performed with the Boston troupe and, then, in 1802, Elizabeth came to New York as the leading lady at the Park theatre.

Reviews of Elizabeth Whitlock

Bernard wrote that “Mrs. Whitelock, [sic] an admirable actress, who was in no way unworthy of her illustrious sister . . .”[9] Elizabeth certainly was more famous than her husband, who, according to Clapp, “was even then past the meridian of life, and dependent upon his wife’s attractions.”[10] “Roscius” in the Philadelphia Minerva described Mrs. Whitlock as “still the female constellation” in a company that evinced “affectation, bombast, and unnatural grimace” in a season that “dragged heavily along, involved in clouds of ranting dullness.” [11] “Theatricus,” in an article in the Philadelphia Gazette, asserted that “no performer, “not even excepting the far-famed Mrs. Siddons” had been able to incite in him “such highly pleasurable emotions.”[12]

When Mrs. Whitlock came to the Philadelphia Theatre in 1801, “Mercutio” in the Philadelphia Repository exulted that “lovers of the drama, have reason to congratulate themselves upon the reappearance of Mrs. Whitlock, after so long, and so regretted an absence.” The critic added that “this celebrated actress, is indeed an acquisition to our boards,” and concluded “in the tragic walk, Mrs. Whitlock stands unrivalled, at least, in this country.”[13]

Not all critics found Elizabeth Whitlock so engaging. Odell comments that New York audiences did not prefer her over other leading ladies, such as Mrs. Melmoth, Mrs. Johnson, or Mrs. Merry. Although all critics acknowledged her talent, they differed on their opinions of Elizabeth’s comparative merit as a leading lady.

Mrs. Whitlock VS Mrs. Melmoth: Fight for the NY Audience

Charlotte Melmoth © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Eliza Whitlock found a rival in Charlotte Melmoth, of the New York Theatre, who regularly depicted the leading tragic roles: Lady Macbeth, Euphrasia in The Grecian Daughter, Matilda in The Carmelite, Lady Randolph in Douglas, Belvidera in Venice Preserved, and Mrs. Beverley in The Gamester. In the Fall of 1802, after disagreements with the Management of the Park Theatre, Charlotte Melmoth left the New York theatre company for that of Charleston, and Elizabeth Whitlock was engaged to take those leading roles. New York’s Morning Chronicle announced the changes that audiences could expect:

. . . considerable alterations have been made in the Company. Mrs. Melmoth, who has during many years filled the higher walks of Tragedy, has removed to the Charleston stage. Her place will be supplied by Mrs. Whitlock, sister to Mr. [sic] Siddons, and late of the theatre, Philadelphia; a lady whose powers in the tragic line are mentioned in terms of high commendation.[14]

The article concluded, “Upon the whole, Mrs. Whitlock had an arduous task in undertaking character that has been so well filled by Mrs. Melmoth, and acquitted herself in the difficult undertaking in a manner that does credit to her talents.”[15]

For the ensuing months, the New York newspapers often printed updates about Mrs. Melmoth’s successes in South Carolina, as illustrated by this notice reprinted from a Charleston newspaper:

Mrs. Melmoth is a great acquisition; her Lady Randolph delighted us; a more correct personation [sic] of that character is hardly attainable—a voice commanding, yet female; action forcible, but modest, and flexibility of accent, directed by a judgment mistress of the emotions she represents, are qualities clearly discovered by Mrs. M.[16]

A Charleston critic enthused, “Mrs. Melmoth’s Matilda, we consider, has just claims to perfection. . . .”.[17]

Back in New York, Mrs. Whitlock did not fare so well with New York audiences. A review of her performance in Venice Preserved complained that Mrs. Whitlock’s “countenance, voice and manner are ill-suited to the soft and pathetic. . .by Mrs. Melmoth we have seen this character exhibited with satisfaction”[18]

When the 1802-3 season ended, Eliza Whitlock departed New York, and Mrs. Melmoth came back to the Park Theatre. Charlotte Melmoth’s arrival in New York in May of 1803, was heralded in four different New York newspapers:

Mrs. Melmoth arrived here on Saturday from Charleston. Her reception on the boards of theatre at that place, was highly flattering. The house on the night of her benefit, was crowded with the most brilliant audience ever witnessed at Charleston—and very circumstance connected with Mrs. Melmoth’s performance, in that place, was of the most pleasing nature. The profits of her benefit exceeded one thousand dollars.[19]

Although Eliza.Whitlock was deemed by her contemporaries to be a good, if not great, actress, she often was derided for her personal appearance. John Bernard remarked, “Her defects were her person, which was short and undignified, and her heavy, thick voice.” [20] Another critic commented that “her person. . . approaches the masculine.” [21]

Despite the inevitable comparisons with her more famous sister and despite the occasional jabs from critics for her physical appearance, Eliza Whitlock enjoyed the admiration of audiences throughout the United States –-not only for her talent but also for her respectability. Dunlap commented that Mrs. Whitlock was “of great value in her profession, and out of it an honour to her family.”[22]

Eliza retired to England and died in 1835 at the age of seventy-four.[23]

NOTES

[1] William Clapp, A Record of the Boston Stage. New York, 1853; reprint New York: Benjamin Blom, 1968.

[2] John Bernard. Retrospections of America. New York: Harper Brothers, 1887, 190.

[3] Philadelphia Repository, 31 October, 1801.

[4] Highfill, Philip H., Kalman A. Burnim, and Edward A. Langhans. A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London,1660-1800.Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1973. Print: 48.

[5] Bernard, 190-191.

[6] Bernard, 256.

[7] Julia Curtis, John Joseph Stephen Leger Sollee’s Management of the Charleston Theatre,” Educational Theatre Journal. 21 (1969): 291.

[8] The State Gazette, 26 April 1797; quoted in Curtis, 291.

[9] Bernard, 264.

[10] Clapp, 40.

[11] The Philadelphia Minerva, 13 February, 1796.

[12] Philadelphia Gazette, 7 April 1795.

[13] Philadelphia Repository, 31 October 1801.

[14] Morning Chronicle, 1 October, 1802.

[15] Morning Chronicle, 21 October, 1802.

[16] Chronicle Express, 13 December, 1802.

[17] The City Gazette, 4 December 1802.

[18] Morning Chronicle. 18 December, 1802.

[19] Commercial Advertiser, 23 May, 1803.

[20] Bernard, Retrospections of America, 264.

[21] Philadelphia Repository, 31 October 1801.

[22] William Dunlap, History of the American Theatre. New York: Burt Franklin, 1963, 239.

[23] Joseph Norton Ireland. Records of the New York Stage from 1750 to 1860. New

York: B. Blom, 1966. Print,151.