(1774-1843)

Eighteenth century fashion © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Elizabeth Harrison, according to several historians, had performed successfully in England before she arrived in the United States at age twenty. She was “was brought to Boston from England in the year 1794 by Mr. C. Powell,” and in the year following her arrival, married the theatre manager’s brother, Snelling Powell. William Dunlap, in his History of the American Theatre, comments that soon “her beauty and talents soon placed her at the head of her profession in the theatres of New England.”[1]

Historians have offered conflicting reports about Elizabeth’s previous experience on the London stage. William Clapp, in his Records of the Boston Stage, claims that Elizabeth had been born in Cornwall in the year 1774 and had enjoyed great success on the English stage:

Mrs. Sarah Siddons © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Miss Harrison, previous to her visit to this country, appeared before George the third, by command and she had also frequent opportunities of performing the second characters to the queen of tragedy, Mrs. Siddons, who was so much pleased with her acting, that she obtained permission for Miss Harrison to accompany her through a circuit of the provincial theatres.[2]

Similarly, Elizabeth Harrison Powell’s accomplishments in England also are highlighted by Charles Wingate, in Shakespeare’s Heroines of the Stage, who states: “in her native land she had played second to Mrs. Siddons, and, by command, had appeared before George the Third.”[3]

Unfortunately, the actress who performed with Mrs. Siddons and before the King could not have been Elizabeth Harrison Powell. Donald A. Sears, in his article “The Biographical Muddle of Mrs. Snelling Powell” points out that an actress by name of Mrs.Powell did indeed perform with Mrs. Siddons; however, she was performing as early as 1791, when Elizabeth’s name was yet “Harrison,” and not “Powell,” and there is no record of a “Miss Harrison” performing with Siddons.[4] A Biographical Dictionary concurs: “Mrs. S. Powell apparently never acted in England ‘as some historians have claimed.”[5]

Old Federal Street Theatre Public Domain Image

Certainly in the young United States, thought, Elizabeth Harrison Powell was beloved and became a “star of the Boston stage,” particularly for her depiction of Shakespearean heroines.[6] Wingate notes that Mrs. S. Powell was the first Boston Rosalind—and that she was described in a review by Thomas Payne as having “more than her usual excellence.”[7] Boston’s first Lady Macbeth, appearing on Dec. 21, 1795, was Mrs. Snelling Powell.[8] She also appears to have been Boston’s first Portia in The Merchant of Venice and the first Katherina in Shrew in Boston in 1795.[9]

Elizabeth obviously was a popular actress in Boston, as indicated by the amount of money collected at her benefit: As Clapp explains, the annual benefits of the actors, in those days, were in reality benefits. That of Mrs. Powell was always honored by a full house . . . .”[10] At the benefits of 1805, Mr. Snelling Powell’s brought in $1,100; John Bernard’s $1050, Thomas Cooper’s – $1,050; and Mrs. Powell, $1,163, the most money for any performer in that season.[11]

In 1800, Elizabeth Powell joined the New York Theatre company. Joseph Ireland in his Records of the New York Stage relates,

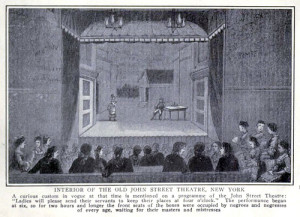

John Street Theatre Public Domain Image

On the 31st [October 1800 in NY] a brilliant addition was made to the company in the person of Mrs. Elizabeth Powell, whose first appearance took place in the character of Angela in The Castle Spectre. This lady was from the Boston Theatre, where she had first appeared, when Miss Harrison, in Gustavus Vasa on the first opening of a theatre in Boston, Feb. 3rd, 1794.[12]

In addition to the admiration she garnered for her professional talents, Elizabeth also received praise for her courage. John Bernard, in his Retrospections of America, recounts a situation in the first decade of the nineteenth century in which he and a small band of actors, including Mrs. Powell, performed in Concord, Vermont. An angry mob had assembled outside the theatre, apparently intent upon stopping the actors from performing. The mob began “abusing and vilifying” the actors because they were English, calling them “spies and montebanks.” Bernard recalled that Mr. Powell was “intimidated and would not go on with his character, but his wife, with a courage that that I could not but admire, persevered like a heroine.”[13]

Lady’s Gloves © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Throughout her career, Mrs. Powell was lauded enthusiastically for her spotless reputation. A newspaper article claimed “She is an ornament to society, and her character is an illustration of the maxim of Solomon, that ‘a virtuous woman is a crown to her husband.”[14] In May of 1813, The Boston Daily Advertiser wrote of Mrs. Powell, “Those abilities which have acquired her a deserved reputation among the lovers of the drama, are, however, among the least of her merits. She is not less exemplary as a mother and a wife, than distinguished as an actress.”[15] ‘Dunlap stated that “She was an elegant woman and a good actress, and will long live in the memories of the public of Boston as well as in the affections of those who knew her private worth.”[16]

Mrs. Powell and her husband were credited with elevating the profession of acting as indicated by the obituary of Mr. S. Powell:

Silhouette of a Lady Public Domain Image

It is not too much to attribute to the private worth and respectability of Mr. and Mrs. Powell, the credit of having dissipated much of the prejudice which characterized our puritanic [sic] townsmen in 1795. They have at least proved that actors do not necessarily belong to the inferior ranks of society; for they have been examples of industry and prudence, rising from a depressed condition to affluence and respectability.[17]

After the death of her husband in 1821, Mrs. Powell shared the management of the Boston Theatre for several years.[18] She died at age 70 in on December 10, 1843.[19] The Massachusetts Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 indicate her age as 69 and deem cause of death as “inflammation of the lungs.” She’s buried at Trinity Church Cemetery.[20]

Clapp summed up Elizabeth Powell’s importance to the city of Boston:

She was the original in this city, as will be seen, of many characters which still retain a position among the favorite theatrical representations of the day, and her impersonations of Shakespeare’s heroines entitle her to a rank among the highest in her profession.[21]

NOTES

[1] William Dunlap, History of the American Theatre. Vol. II. New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832. Reprint, New York: Burt Franklin, 1963, 134.

[2] William W. Clapp, Jr. A Record of the Boston Stage. New York: Benjamin Blom 1853; reissued 1968: 21

[3] Charles Wingate, Wingate, Charles E. L. Shakespeare’s Heroines on the Stage. New York: T.Y. Crowell & Co, 1895. Print.

261.

[4] Donald A. Sears, “The Biographical Muddle of Mrs. Snelling Powell.” The New England Quarterly. 33 (September 1960), 371.

[5] Highfill, Philip H., Kalman A. Burnim, and Edward A. Langhans. A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800.Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1973. Print: 106.

[6] Wingate, 261.

[7] Ibid, 152.

[8] Ibid, 212.

[9] Ibid, 261, 277.

[10] Clapp, 152.

[11] Clapp, 84.

[12] Joseph Ireland, Records of the New York Stage. New York, 1866; reprint, New York: Benjamin Blom, 1966, 194.

[13] Bernard, Retrospections of America, 318.

[14] Quoted in Clapp, 152.

[15] The Boston Daily Advertiser, 7 May 1813.

[16] Quoted in Ireland, Vol. I, 194.

[17] Quoted in Clapp, 184.

[18] Ireland, 195.

[19] Bernard, Retrospections of America, 317.

[20] Massachusetts and Town and Vital Records. 1620-1988, Ancestry.com.

[21] Clapp, 21.